In 1944, when Geraldine Book, a resident of Washington DC, graduated from her nursing school all she wanted to do was travel the world. Consequently, she joined the US Army in its war effort. The Second World War was raging in full swing at that time and Book along with another classmate of hers volunteered for overseas duty.

After six long weeks at sea, she landed in Calcutta where she was expected to tend to the wounded and ill in the China-Burma-India theatre. “You could smell Calcutta a hundred miles away. It was a huge city. People were dying in the streets and on the doorways,” she says in a 2004 interview archived by the Veterans History Project of the Library of Congress. “Everything smells like it’s decaying,” she says about her first experience of Calcutta, as she narrates how she saw British trucks loading up bodies to dispose off in the burning ghats, and the occasional sight of arms and legs floating in the river that left her shocked.

India was in a strange position during the War. As historian Yasmin Khan puts it aptly in a 2012 article: India was “not quite a home front, nor quite a war zone, India was nevertheless critical to the war effort as a source of military power and industrial production.”

At a time when anti-colonial mood was running high in the country, it found itself caught in the frontline of a war between two imperial powers in SouthEast Asia- the British and the Japanese. After the fall of Singapore to Japanese aggression in February 1942, Calcutta emerged as perhaps most vulnerable to further advancement of troops from Japan. Soon after, the city turned into a major site of a global war, with its rest houses, hotels, training camps teeming with British, American, Chinese and African troops.

American soldiers arrived in Calcutta at a time when apart from the war, a devastating famine was causing havoc. The initial impression was one of shock at seeing an India far in contrast to the fantasy land shown in Hollywood movies.

Khan in her book, ‘India at war: The subcontinent and the Second World War’, quotes an American journalist on what the soldiers experienced: “The Americans, accustomed to see India through Hollywood’s cameras as a fabulous land peopled by Maharajas and elephants were appalled and sickened by the stink and poverty of the place.”

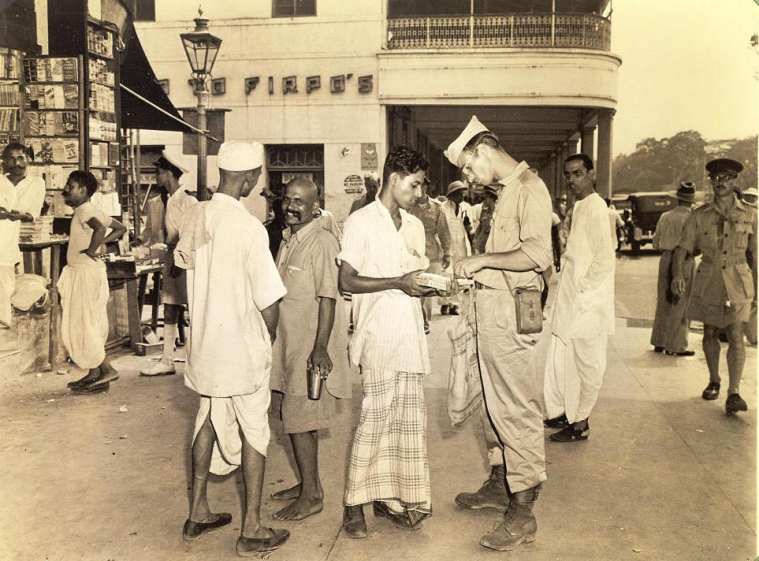

But in this war torn, famine stricken, and high strung political atmosphere of the 1940s, the American soldiers also found themselves in an interesting and yet peculiar position. A large majority of them were white, much like the British, but devoid of the necessity to defend an empire. “The American soldier of course had an oriental gaze, but they are asked to not involve themselves politically. Consequently, they were more friendly and frequently shared food and drinks with local people,” says Reeti Basu, who is currently doing her PhD in Jawaharlal Nehru University on the topic of American military in Calcutta. What emerged was a short but fascinating period of cultural exchange of food, music, cinema, art and a lot more that would largely transform the socio-cultural landscape of Calcutta.

Doing their bit in a famine struck Calcutta in war

From 1942, some 150,000 American troops came down to India. In order to help them settle in this alien land, friendly pocket books were handed out with detailed instructions on how they must conduct themselves in the country. One of these, ‘The Calcutta Key’, was a pocket-sized 96-page guide on the city with information on everything from which markets to frequent, how to bargain, where one can find alcohol, women and a lot more. A striking piece of instruction on the ‘to do’ list of the Calcutta key is ‘to avoid political discussions’.

‘The Calcutta Key’, was a pocket-sized 96-page guide on the city with information on everything from which markets to frequent, how to bargain, where one can find alcohol, women and a lot more. (Amazon.com)

‘The Calcutta Key’, was a pocket-sized 96-page guide on the city with information on everything from which markets to frequent, how to bargain, where one can find alcohol, women and a lot more. (Amazon.com)“American soldiers were frequently scathing about the Raj,” writes Professor of International Relations and History, Srinath Raghavan in his book, ‘The most dangerous place: A history of the United States in South Asia’. Criticism against the British was far from being unwarranted as the Americans were witness to the famine-induced poverty caused by the policies of an apathetic British government. The Calcutta Key in fact suggests in great detail the famine conditions they can expect to see during their time and how they must react. Raghavan in his book quotes a GI’s reaction to the poor huddled up on the street, peering through glass windows at the shops, “If I were they, I’d smash those glasses and help myself to all that’s there.”

Given the affable relations the American GIs were prone to strike up with the local population and the possibility of American support for the ongoing freedom struggle in the country, both the British and US governments were keen on keeping the young soldiers as apolitical as possible.

Another guidebook explicitly spelt out to the GIs: “Americans are in India to fight the Axis. You should stick to that and not try to settle the Indian political problem. What we want is to cooperate with both the British and Indians to beat the Japanese. Your place is to keep the eyes and ears open and mouth shut.”

But that did not stop Indian politicians from reaching out to the GIs for support. Raghavan refers to a piece of writing by the independence activist Jayaprakash Narayanan wherein he addressed the GIs, “You are soldiers of freedom… It is, therefore, essential that you understand and appreciate our fight for freedom.” He urged them, “let your countrymen, your leaders and your government know the truth about India.”

Historian Manish Sinha in his article, ‘The Bengal famine of 1943 and the American insensitiveness to food aid’ notes that in August 1943, then Calcutta Mayor Syed Baddruja cabled President Franklin Roosevelt urging him and British prime minister Winston Churchill to arrange immediately for the shipment of food grains to India. While Roosevelt passed along the cable to the State Department, which was well aware of the difficult food situation in Bengal. “Roosevelt refused to take any action, not intending to provoke British resentment against American interference,” writes Sinha.

Interestingly, despite the refusal of the US President to act, the American army in Calcutta were swift to organise a voluntary food donation scheme by saving a part of their weekly rations of canned food for the hunger stricken in Calcutta. Tathagatha Neogi, a Kolkata-based heritage expert, says in December 1942 when the Japanese bombed Calcutta, his grandfather was working in the dockyards as a railway engineer. “Because he was working in the port, he would receive donations from the American army which included canned food like sardines, baked beans etc which helped my family tide through the acute food shortages of the famine,” he says. He notes that the American soldiers were in fact responsible for popularising canned food in Calcutta during and after the war. “The British soldiers also survived on canned food as rations, but the Americans were more willing to share.”

Expectedly, the British did not take well the American attempts to provide famine relief to Indians. “The British were always suspicious of the Americans and thought that they were here to aid the freedom movement. They saw these efforts of famine relief as further proof of the same. Consequently, the British had spies in the American army headquarters which was in the Hindustan Building,” says Neogi, who is also founder of the heritage walks company, Immersive Trails, and has been organising a walk, ‘Calcutta in World War II’ since 2018.

The American soldiers’ inclination to informally engage with Indians over food, drinks, music and so much more made them appear more friendly to the latter. Basu says several references to this can be found in popular literature. “There is a story I came across, in which the protagonist, a Bengali boy in the army who was posted in Burma, says American troops are more friendly towards us since they offer us beer and food. The British soldiers in contrast would hardly speak to the Indians,” she says. She also recollects her grandmother telling her about an incident of American soldiers throwing chocolates to her while parading down Chowringhee.

The American soldiers’ inclination to informally engage with Indians over food, drinks, music and so much more made them appear more friendly to the latter. (Wikimedia Commons)

The American soldiers’ inclination to informally engage with Indians over food, drinks, music and so much more made them appear more friendly to the latter. (Wikimedia Commons)

Neogi says the relationship between Indians and American soldiers also depended on where they were located. “In the countryside, for instance in the border between what is now Bangladesh and Burma, there were a lot of horror stories of American atrocities. They were protecting the area from Japanese incursion and often would not differentiate between INA spies and local people,” he says.

“In Calcutta, since it was not right on the frontier, there was more of a fellow feeling.”

Basu notes that there were also instances when the American GIs got into unpleasant rows with Indians. “For instance, they had a very strained relationship with the Taxi drivers. In fact, the taxi drivers’ association had taken out a procession against the American GIs after an incident in which a soldier knifed a driver,” says Basu.

Also read: When US soldiers got caught in the traffic of Calcutta

The black and white soldier in Calcutta

While on one hand the American soldier was getting a taste of the Indian political situation in the streets of Calcutta, on the other hand, they brought along with them racial politics of their own. Among the 150,000 American servicemen, 22,000 were Black GIs. Their experience of Calcutta and with people of the city, was in marked contrast to that of the whites.

Khan in her book notes that the segregation of the American South permeated the American Army, and while stationed in India, black and white GIs faced blatant and enforced separation. They had fewer canteens, deplorable living conditions, poorer means of entertainment and also were expected to take on more menial labour. “In Calcutta, there were segregated Red Cross canteens with Black Red Cross women shipped in especially to staff them,” writes Khan. “The one service swimming pool in Calcutta had white days and black days. Black troops were given second class medical treatment, were more likely to catch malaria, had less chance of leave, received harsher treatment from officers and drew the ire of Military Police,” she notes.

Consequently the black troops and Indians found a common cause, contrary to what the imperial government had expected given the existing racist tendencies among South Asians. The Black GIs spent more time in the local markets and tea shops and were more likely to strike up conversations with Indians. “As a consequence, black soldiers made new friends, received invitations to local parties and dances and were more likely to have an Indian or Anglo-Indian lover,” writes Khan.

At the same time though, inherent racist attitudes among Indians towards the black GIs were also frequent to come by. “Popular Bengali literature of the time would frequently refer to black soldiers as ‘negro’ or kaalo kuch kuche (pitch black),” says Basu. She explains there was a lot of fear among Indians towards the black soldiers. “There were rumours about them feeding on human flesh,” she adds.

Neogi says during the 1946 Calcutta killings, there were 26 American casualties in the city and most of them were Black. “Most of them were just at the wrong place and at the wrong time. And they were killed in brutal ways. One of them was driving an ambulance. He was stopped by the mob and the entire ambulance was doused in fire,” he says. “That does give us some insight about racist tendencies towards the blacks among Indians.”

A period of popular cultural evolution

But war, politics, famine aside, the arrival of the American soldiers was also a moment of immense transformation in the cultural life of Calcutta. The legendary filmmaker Satyajit Ray, who had returned from Shantiniketan to Calcutta after the Japanese air raids, wrote in his autobiography about the new spate of American popular culture that erupted in the city’s streets at this time. “Chowringhee was chock-a-blocks with GIs. The pavement book stalls displayed wafer thin editions of Life and Time, and the jam-packed cinemas showed the very latest films from Hollywood,” he wrote.

Ray’s biographer, Andrew Robinson, wrote about how “because of the war, Ray was able to see films that had not been released even in London”. “GIs used to seek out Satyajit at his home and tell him about a US movie playing in town or at their base- ‘Wanna come’?” notes Robinson in his book, ‘Satyajit Ray: The inner eye’.

American soldiers at a shop in Calcutta (Wikimedia Commons)

American soldiers at a shop in Calcutta (Wikimedia Commons)

Iconic theatres of the city like the Metro cinema at Esplanade Road, Lighthouse Cinema and New Empire Cinema in New Market and Globe Cinema at Lindsay street had come up even before the war with the objective of showing Hollywood movies exclusively. But it was only during the war that they became more readily accessible to Indians. “The Metro cinema was run by MGM and they had a deal with the US Army that every week three movie passes would be given away to the soldiers. Often, the soldiers would hand over these passes to their orderlies who were Indians, or their Indian friends and acquaintances and that’s how Hollywood became more popular among the locals,” says Neogi.

Ice-creams and Coca-Cola were also products brought in by the US Army specifically with the aim of making their GIs feel at home. Neogi explains, “Coca-Cola established two plants exclusively for the US troops in Calcutta, one in Kidderpore and another in Central Calcutta. They also established an American ice-cream plant in what is now Chandni Chowk market.”

Like with the movies, each soldier was given three passes for Coca-Cola and ice-creams every week. With the American GIs eager to share these passes with their Indian friends and acquaintances, ice-creams and Coca-Cola soon found popularity among Indians. One other food product made hugely popular in Calcutta by the American GIs was the brownie.

In the area of music as well, an impressive transformation was heralded with the coming in of the GIs. “Jazz was made hugely popular by the American soldiers. The Statesman would frequently put out advertisements for Jazz nights in the Grand Hotel, where the soldiers were staying and the famous Jazz musician Teddy Weatherford would play there,” says Basu.

This was also the time when Park Street emerged as the centre of Kolkata’s live music industry. Basu refers to the historian Tapan Raychaudhury’s book, ‘Bangal Nama’, where he has mentioned that despite an ongoing famine in the region, Park Street does not appear to be afflicted by any calamity at all. Restaurants such as the Firpo’s (opened by an Italian during WWI) would come alive with American GIs every evening and live music being played by foreign troupes.

American GIs in front of Firpo’s (Wikimedia Commons)

American GIs in front of Firpo’s (Wikimedia Commons)

“The latter day music scene in Park Street was a product of this cultural connection that swept through the city during the war years,” says Kolkata-based filmmaker and photographer Sanjeet Chowdhury. “It was only in the post war years that Park Street turned into this busy, lively street, forever buzzing with parties and music,” he says.

In terms of what the Americans absorbed in Calcutta, Basu says “they were very fond of the works of the painter Jamini Roy.” “In fact, a grandson of Jamini Roy whom I had once interviewed had told me that the American GIs were responsible for increasing sales of his paintings, which helped him resolve the financial problems he was going through,” she says.

The five years of American influence on the city was marked by several far-reaching political and social events. Amidst this all, the dynamic presence of the Americans is largely forgotten in historical textbooks and archives. “I know that many felt their presence was so insignificant they did not even realise when they came and left,” says Basu. “And yet there are also those who feel that the impact that the American troops left behind was massive and long-lasting.”

Further reading:

Yasmin Khan, India at war: The subcontinent and the Second World War, Oxford University Press, 2015

Yasmin Khan, Sex in an imperial war zone: Transnational encounters in Second World War India, History Workshop Journal, 2012

Srinath Raghavan, The most dangerous place: A history of the United States in South Asia’ ,Penguin Random House, 2018

Manish Sinha, The Bengal famine of 1943 and the American insensitiveness to food aid , Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, 2010

Satyajit Ray, Our films, their films, Orient Longman, 1994

Andrew Robinson, Satyajit Ray: The inner eye, University of California Press, 1989

Janam Mukherjee, Hungry Bengal: War, famine and the end of Empire, Oxford University Press, 2015

How Trinca’s of Kolkata kept a live music industry alive for decades

Source: https://indianexpress.com/article/research/coca-cola-canned-food-and-jazz-nights-what-american-gis-brought-to-the-streets-of-calcutta-during-wwii-7397632/